Douglas Goldie, of Douglas G. Goldie & Associates, operated a boutique firm providing marketing, design and communication consulting services in Toronto and Montreal in the 1960’s and into the early 1970’s. Douglas and his team assisted recognizable clients on projects that ranged from design to product branding. The path that led a youth from Montreal into a career of wordsmithing, product design and branding was a varied one, taking several turns along the way.

The early years

Born in Montreal, Douglas’ family relocated to Toronto while he was still a boy. Eventually, he attended Western Technical-Commercial Secondary School in Toronto’s West End. It was there he learned typewriting — a useful skill he would continue to use throughout his life. He was a lifelong learner, a voracious reader: he was often reading books, newspapers on a variety of subjects. He was cerebral and insightful, with a broad range of interests that informed the foundation for his attitudes and outlook.

As a teenager, he played the flute in a marching military band. Then, when the European War broke out, he volunteered for service. Underaged and with poor eyesight, this first attempt to enlist proved unsuccessful. Douglas was undaunted — with the assistance of a fellow band member, he “acquired” a copy of the eye chart and proceeded to memorize it in preparation for being retested. As for his age, he misrepresented this detail and he was soon enlisted. Needless to say, his parents were quite unhappy about his new assignment but reluctantly let him go as he had just come of age. He further purchased a set of eyeglass frames that looked remarkably similar to the government issued pair so that his eyesight would not be discovered.

The war years

Following basic training at Camp Bordon (in Barrie, ON), he was deployed to Great Britain as part of The Queen’s York Rangers near Aldershot, southwest of London. There, he was a clerk and worked in logistics where he was responsible for loading troupe trains and getting them away on schedule. As a sergeant, he quickly learned that he needed the cooperation of more senior officers who would not take direction from a junior rank. Undeterred, Douglas and a peer devised a solution: both men would don dispatch riders jackets (which bore no markings or insignias), and they would refer to each other as “sir” and “sergeant major,” respectively. The deception worked and they were able complete their task in an expedient manner. They were eventually discovered and consequences followed. However, the technique was so successful that leadership could not argue with the effectiveness and efficiency, particularly during the Battle of Britain. While on leave in London, and on at least one occasion, he needed to take shelter in a building doorway during one of the “big” bombing raids.

Civilian life – in newspapers

After the European war ended, Douglas returned to Toronto, married his sweetheart and got his start in the newspaper business (in both Hamilton Spectator and Brampton). Eventually, this led Douglas to partner with his brother, Gordon Goldie, (who later founded The Goldie Company, fundraisers in Toronto) and a friend Hank Henry to purchase the Geraldton Time Star in 1946, a weekly newspaper, located near The Lakehead (Thunder Bay). Geraldton was a small community, quite removed from the urban centre of Toronto. Douglas wrote the copy as well as handled the business end. Gordon was the reporter and photographer and Hank ran the printing plant. The printing press was an offset model and quite advanced for a local paper in a smaller market – it had the capability of printing colour. The main economic drivers in this area were natural resources, both mining and forestry. Initially, both the mine and forest workers were paid on the same days, which meant they would go into town for some weekend entertainment which typically ended with street brawling between the groups, causing damage and disruption to the community. Seeing the pattern, both sets of employers agreed to stagger the pay dates, quickly ending the destructive situation.

Douglas often recalled this time in his life, especially citing several memorable moments. One story that he liked to tell was how one Christmas, after a team meeting at the local watering hole, they arrived on the idea to give the reindeer on the front page a “red nose” just like Rudolph in the song. Creative. With the paper having already been printed, it was just a matter of rerunning the front page through the press a second time, printing the red dot on the end of the reindeer’s nose. Easy. The challenge was in matching the paper alignment: the red dot ended up all over the front page, except where it was wanted.

Another story, demonstrating the rough and tumble aspect of the area, recounts how a miner went home with several sticks of dynamite strapped to his body and lit the fuse. When Gordon arrived at the scene to report on the events, there was a perfectly circular hole in both the roof and the floor and the wife was sweeping up and remarked, “He messed up my house”. Douglas was a committed newsman, growing their business to include other communities in their masthead such as Longlac, Hornepayne and Hurst, well aware that providing service in those communities would involve a bit of a commute from Geraldton.

With a growing family, Douglas left Geraldton 1951 or ’52 and returned to Toronto. There he worked at Maclean Hunter (The Financial Post) under A. A. “Bud” Weaver, Advertising Sales Manager and quickly rose to become the assistant advertising sales manager. These were “good” times for Douglas as he enjoyed a corporate salary and experienced yearly international travel to places like Italy (going to the Fiat plant in Milan or Olivetti) or Japan (Dentsu Agency) among other countries. At the time, the Financial Post ran an annual section on a specific industry or sector and, as part of his role, he would travel to other countries to obtain the advertising commitment from the “targeted” industries/companies.

Branching out on his own

By the early 1960’s, it was time to move on and Douglas formed Douglas G. Goldie & Associates, a boutique firm that provided marketing, design and communication services. With a partner and offices in both Toronto and Montreal, they served a number of recognizable clients. This was a time of growth and Canada’s 100th anniversary was approaching in 1967 (Expo ’67, held in Montreal). At the height of his career, his office occupied two floors at Yonge St. and Eglinton, employing approximately 30 employees with a fair number of graphic/commercial artists and designers. He was also a member of The Advertising & Sales Club of Toronto.

With his background in newspapers, his expertise was mainly in print media. Over the years, his firm served clients like Lionel (manufacturers of Peterborough and Princecraft Boats and Sno-Prince snowmobiles), several municipalities that wanted to attract businesses into their regions for economic development purposes (e.g., St. Catherines and other Niagara region) as well as industrials like Price Brothers, which is recognizable today as AbitibiBowater. Douglas even held a patent on a plastic waterski, trade name “Plaski” – “a hollow core plastic water ski comprised of an elongated rectangular body with the top and bottom surfaces separated by side walls with the topside having transverse reinforcing ribs.”

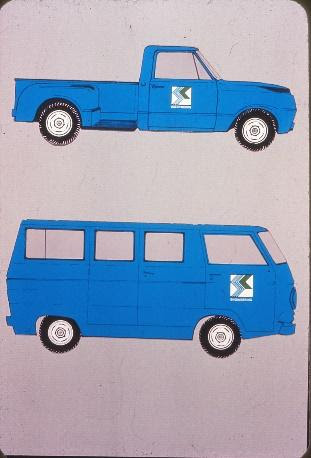

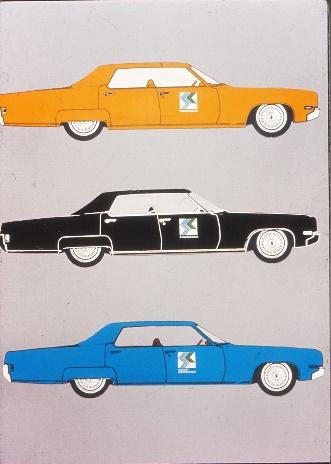

Douglas understood the power of a consistent corporate identity or brand with logos, colours, etc.. He was ahead of his time. For companies like Lionel, there was the logo with colours that corresponded to its various business units. The designs even included the branding for the delivery trucks: he felt that a delivery truck was a movable billboard. Why not advertise your product while the truck is on the road making deliveries? Today, we see this application as commonplace, but in the 1960’s, this would have been a labour intensive effort and therefore an expensive solution to outfit an entire fleet of delivery trucks. It took about 40 years for the technology (wrap) to catch up to the concept.

The Lionel branding plan incorporated unique branding opportunities, including formal dress wear in the form of a cummerbund for those executives about town. Interestingly, the accessory was worn during evening events where staff mingled with dealers; this was a very effective means of identifying the sales team. Lionel (Sno-Prince) also formed/participated in a snowmobile event like Lake Placid in 1970 which saw the crowning of a “Snow Princess.”

Municipalities and regions that were looking to attract new businesses also embarked on economic development and branding exercises, adopting a consistent aesthetic that could be used as part of the pitch across the multiple departments. The City of St. Catherines was a client of Douglas G. Goldie & Associates, and their logo design continues to be used over these 50 years, surviving the test of time.

As he had structured for his corporate clients, Douglas planned for consistency in the city’s brand applications, including its vehicle fleet. The strategy was developed around the region’s uniqueness in terms of market access which drew on its geographic location and proximity to key resources such as energy from Niagara Falls, steel from Hamilton as well as the transportation corridors for finished goods. Not wanting to focus exclusively on the business advantages, the brand development process was more holistic and included the historical and cultural aspects of the region. The lifestyle attractions made it a viable destination for relocating one’s family, for employment and for attracting tourists to the region to spend their leisure dollars. These are all recognizable themes that continue to be relevant today.

At a time before digital storage, information was kept in filing cabinets and the question was how to best organize paper for quick retrieval? It was understood that access to fast and accurate information has attributed costs in terms of clerical time, and overhead. Douglas worked with Price Brothers to develop a system to better organize information using a system branded Profile ’67 (Protrac ’67) – this was a Canadian-designed system based on file folders suspended on “tracks” in lateral filing cabinets.

Colours were used to group like files, facilitating the efficient retrieval of information

.

Product design and prototypes

Douglas was involved in many product designing efforts and, as a result, had accumulated a diverse collection of prototypes. One product line was wearable paper-based products: bed sheets, surgical gowns, underwear and surgical-like masks. These were to be used in a hospital setting and could be incinerated after use, economizing on laundry service costs. Unfortunately, they were found to be stiff and scratchy, not remotely as comfortable as the cotton counterparts already in use. The mask, however, may have been the basis for the medical masks used today. It would be interesting to do a patent review and understand if these efforts in the 1960’s may have contributed to the availability of the personal protection equipment that has helped us in this time of COVID-19.

Douglas constantly mulled over potential approaches to marketing campaigns and found inspiration in random settings. For instance, anyone who has lived in Toronto over several decades may recall that there used to be a very large neon “Esso” sign just East of St. Michael’s Hospital on Lakeshore Boulevard. One evening, Douglas was driving Eastbound on the Gardiner Expressway when he was thinking specifically about how to brand the underwear and, after seeing the Esso sign, had the brainwave: “Asso’s”. He was not serious, but he had some fun. His sense of humour was as grand as he was. One is never sure where or when creativity would happen.

Another product that Douglas was involved with was the illuminated street signage that Toronto had installed downtown. In those days before GPS and when it was difficult to see the street names while driving in the city at night, the electric signage was the proposed solution. The client was Steel Art. The following photo is a prototype with different street names on either side. This was a centennial project for 1967, which seems a likely timeline.

Where to go from here?

What was the succession plan? Would a larger organization (like an Ogilvy and Mather) want to bring this boutique firm into the fold? What happened to this D. Goldie & Associates? While the 1960’s were a time of growth, there was recession in the early 1970’s: clients cancelled contracts, some bad debts went uncollected and, eventually, Douglas was faced with a difficult decision. It was with a heavy heart that he concluded that he could no longer provide sustainable employment for his talented team and, so, folded up the tent.

Lessons learned – the legacy

Drawing his life lessons, Douglas (my father) gave me several key insights:

In an economic downturn, when a company needs to save money immediately, one of the first places to economize is its non-core projects. Often, such projects involve outsourced services, drawing upon discretionary operating funds. As a result, consulting contracts are typically among the first expenses to be cancelled or cut significantly.

When sharing intellectual property, it is important to understand that once the ideas are out there, you can’t claw them back. If not done well, the ideas can be copied and manufactured by others at a cheaper price, as they did not have any development costs.

Douglas observed that Canada was (and still is) a smaller market relative to the US and that a product would not make it in Canada until it was accepted in the US. For the most part, this continues to hold true today.